(Published in the Business Standard, February 4th, 2014)

In 1997, Granta 57 turned its entire issue over to India, commemorating the 50th year since Independence. The Golden Jubilee edition was greeted with cautious praise and what would become a trademark suspicion of any book that attempted to cover all of this vast, noisy republic.

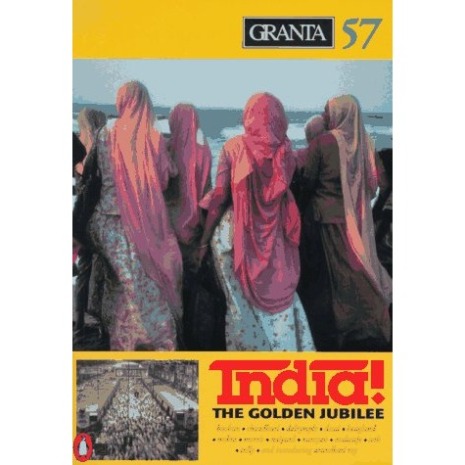

17 years later, Ian Jack looks back at Granta 57: India with a mixture of pride and some regret: “The biggest mistake was the cover. Too ‘exotic’ and entirely my fault. We should have made Salgado’s picture of Churchgate station the only cover image.” Jack, already a seasoned India hand by 1997, has a much longer list of what made him proud: Suketu Mehta on Mumbai, Urvashi on her Pakistani uncle, the extract from Arundhati Roy’s God of Small Things, and the work by photographers Sanjeev Saith and Dayanita Singh. It’s surprising in retrospect how much of Granta 57 has endured; it was only the older, more established authors whose words seem like weak tea now.

On Dayanita’s pictures of newly prospering families, Jack writes: “How sober they look now!” The 1990s was a decade of timid flashiness, compared to the bold, almost frantic flaunting of wealth that marked the early 2000s. Saith’s portraits of people remembering 1947 “would be an ordinary enough exercise for an Indian magazine these days, but then it was rare and I’m glad we did it”, Jack says. Partition memories were common coin in the 1980s and 1990s, shared so freely that few of us listened to them with much attention. But as Chinua Achebe said, the memories of the old are like a library on fire. “I imagine that 17 years later all of the subjects are dead,” Jack writes. “Three of my friends who appeared most certainly, and sadly, are.”

The problem of writing about countries, and continents, Gabriel Garcia Marquez argued in his Nobel speech, is that you were stuck with the outrageous, exotic, shamelessly picturesque truth if, for instance, you were writing about the southern lands of America. Garcia Marquez mentions Pigafetta, a navigator who wrote a “strictly accurate account that nonetheless resembles a venture into fantasy”. In his part of America and our part of the subcontinent, what choice did the writer have except to plunge into this outsized reality?

It was astute of Granta, perhaps the greatest of little magazines, to sneak up on the country issue, approaching it sideways through the years. The early years of Granta featured an iconic issue on the fall of Saigon, a selection of “best of” young writers, a look at countries after the revolution from Soviet Russia to Cuba, two ambitious New Europe and New World issues; but it was only with Granta 48 that the editors boldly and openly tackled a continent.

Years later, in Granta 92: The View From Africa, Binyavanga Wainaina rewrote the rules of the writing-places game with How To Write About Africa. “In your text, treat Africa as if it were one country. It is hot and dusty with rolling grasslands and huge herds of animals and tall, thin people who are starving…. Africa is big: fifty-four countries, 900 million people who are too busy starving and dying and warring and emigrating to read your book.”

And that is an old Granta trick, to circle in great arcs around a subject or a place or an idea, returning in precise sorties in future issues. There are few definitive issues that are not works in progress. The second Granta issue on India, to be edited by Jack again, due out in 2015, raises interesting questions. If it’s to be more than a gazetteer’s report, what should a “country” issue tell you? And does he want it to say anything different the second time around?

Jack writes back from the Bengal Club, where, he notes, lobster thermidor cost 285 rupees or pounds 2.85, “the price of a tea in Starbucks”. When Granta’s new owner, Sigrid Rausing, suggested an India issue to him, he thought of all the good writers of non-fiction who’ve come up since 1997. “When I first came here, the bestselling non-fiction book was Freedom at Midnight, a popular account of a huge moment in Indian history written by a Frenchman and an American.” In 1997, there were fewer Indian writers describing India in non-fiction. James Buchan did the piece from Kashmir, “a good piece but from the outside—today the writer would probaby be Basharat Peer”.

“When Naipaul, referring to Gandhi, said that Indians had the wrong mindset to write history—that they just didn’t notice enough about the world outside themselves—people didn’t think his point was outrageous. Histories of India, travel in India—that was what outsiders did.” He wants to see more Indian non-fiction, and he’d like the next India issue to have politics, feminism and terrorism on the list. “You might say Indian writing has normalized,” Jack writes, “more and more it addresses an Indian audience and is published in India.”

Translation remains a difficult area. “Commissioning non-fiction in an Indian language is a huge risk for an English editor who doesn’t understand much beyond the Hindi for ‘right’, ‘left’, ‘go away’ and ‘milk but no sugar’,” writes Jack. The quality of translation, as Indian editors have often commented, also matters. “As to whether India can be properly represented without such pieces. I have to say probably not. But then which country has ever been properly represented by literary writing? Whole chunks of the British experience are missing too.”

The sequence of Granta’s continent/ country issues, strung out frugally over the years is: Africa, India, France, Russia, London (“almost a country”), Australia, Africa again and now India 2.0. As Jack writes: “As geographers say, ‘Everything happens somewhere’ and I have always liked writing with a firm sense of location.” Another reason to put India back on the Granta map.

Leave a comment