(Published in the Business Standard, December 18, 2012)

Reading on the Metro: Between Central Secretariat and Jahangirpuri, as the Metro swings under the surface of Delhi’s busy roads, you see a pattern in what people read. South Delhi carries the bestsellers of the day on to the Metro, moving from Ravinder Singh and Amish Tripathi’s Meluha series to Hindi translations of Fifty Shades of Grey.

Some of these are pirated books, cheaply printed. Sometimes, their pages fall off, littering the Metro’s sleek carriages with descriptions of gods, wars, bondage, dominatrix gear. Towards Jahangirpuri, it changes. Grihashobha and other women’s magazines return; the old railway classics of a previous generation, Premchand and Mohan Rakesh, rub shoulders with Hindi translations of Arundhati Roy’s essays, Steve Jobs’ biography. The places where you read change the way you read: Delhi’s Metro is still mostly conservative, unspectacular in its fidelity to the bestseller list and the classics of the past. But like the railways, and unlike other forms of public transport—buses, auto-rickshaws—the Metro offers, at least in part, the public privacy essential for readers.

Reading on ereaders and Tablets: Despite the lamentations of print-book enthusiasts, more and more Indians encounter their first books on tablet computers and (less frequently) on e-readers. In my past year of reading on a Kindle and other devices, this has been a mixed experience. The promise of ebooks was, theoretically, the ability to read what they’re reading elsewhere, in Shanghai, in London, in Nairobi, in Mexico City. Words would cross borders, geography would no longer tyrannise authors, making them invisible outside certain markets etc etc.

But while the Kindle, for instance, opens up some access, the Indian reader is as cruelly bound by geography as is the Indian cinephile or music lover. Many books are unavailable in the Indian market; and to be an e-book reader today is to exchange the limitations of a narrow, restricted Indian marketplace for the boundaries of an equally narrow, expensive, Western marketplace defined largely by online chain bookstores. It is that much harder to find a good Latin American, Russian or Chinese bookstore online, for instance; they are as invisible to Indian readers as the average Indian writer would be to the average Chinese or Brazilian reader. That promised paradise of unlimited reading pleasure might exist, but for now, your query for anything too far outside the norm will be returned: “Access Denied.”

Reading in Indian bookstores (physical): This is a sharply divided experience. In malls, where many urban Indian families have their most significant exposure to books, most bookstores are shrines to the present. Their shelves are stocked with only books of the moment, bestsellers from India and elsewhere, as though these bookstores exist in the permanent absence of history. Each store has a token, misshapen collection of “classics”, narrowly defined and rarely browsed.

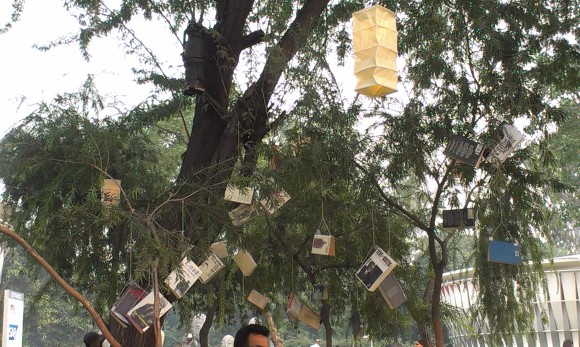

In contrast to these are the indies—not just bookstores but the new, reconfigured lending libraries—that become gathering points for entire community. Literati in Goa’s Candolim, the cozy Bookshop in Jorbagh, Kitabkhana in Bombay’s Fort area, the mobile Boi Gari in Calcuttta and other mobile libraries run by organisations such as Pratham, lending libraries based on the Eloor pattern—places like this do more for reading than a hundred government schemes.

Reading in Indian bookstores, online: The Flipkart effect—the jump in Indian book-buying habits caused by the growth of online bookstores—made books in English available to a much wider readership, especially in small towns and areas without access to good bookstores. Though most analyses of online bookstores have focused on the English-language readership, an equally interesting story is told by the sales of books in other Indian languages, on Infibeam, Flipkart, Snapdeal and similar sites.

Books in mainstream Indian languages such as Hindi, Marathi, Gujarati, Tamil, Telegu and Bengali are a small but fast-growing category. At the risk of over-simplification, each language has very distinct preferences. Hindi and Bengali bestsellers include many literary classics and much poetry; Tamil bestsellers show an appetite for science writing and biographies; Gujarati readers have a taste for literary non-fiction (histories, memoirs) as well as an avid interest in stock market books.

Across all languages, though, the rise of the English language bestseller in translation is an interesting if worrying trend—from Chetan Bhagat to Who Moved My Cheese?, Ayn Rand to Paulo Coelho, globalized pulp fiction appears to have overtaken, and perhaps even replaced, local pulp fiction in many Indian languages. As for world classics, they survive, but in bizarre and unexpected ways—a yes to Garcia Marquez, to Dickens, to Jules Verne, but more contemporary writers, from Atwood to Bolano to Chabon, are not that easily available outside of English (except for the efforts of a few Indian language publishers).

That summarizes the predicament of the average Indian reader today: caught in a permanent present when it comes to reading our country’s own writers, stuck in a frozen past when it comes to reading world writers in many languages outside of English.

Leave a comment